Richard West notes quizzically that Chaucer wrote nothing of his travels in Italy. He questions whether Chaucer was mindful of the writings of Boccaccio and critical studies of Dante and sought not to impinge upon similar territory. He notes Chaucer was selected by King Edward III for the journey following his diplomatic missions to Flanders, France and Spain along with two Genoese residents in England. However West also lets it be known that there is no concrete evidence that Chaucer ever had any knowledge of Italian contrary to reports by Chesterton. Chaucer's trade mission was to discuss issues pertinent to English export commodities of wool and cloth, with little evidence of his knowledge of cargo carrying or ports management which should not be expected anyway.

However Chaucer's borrowing of Dante's themes, in the Second Nun's Tale, the story of Ugolino in the Monk's Tale, the Parliament of Fowls, House of Fame, the Legend of Good Women, and the Nun's Priest's Tale often take on a deprecating humourous quality which reminds readers that he had tasted of the great classics such as Virgil, Ovid, Boethius, St. Bernard, and the Arthurian Romances. But his borrowings also extended to his contemporaries including Machaut, Deschamps, and Froissart.

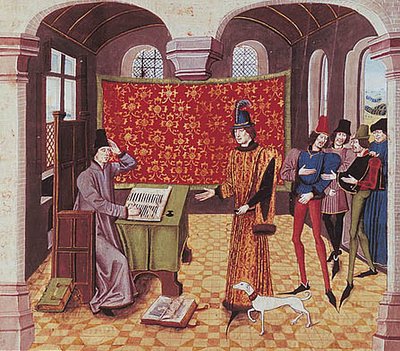

Guillaume de Machaut (circa 1300-1377)

Probably educated in Reims, he entered the service of John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia, as a royal secretary, circa 1323. The king helped him to procure a canonry in Reims, which was confirmed in 1335; Machaut settled there circa 1340, although he continued in royal service until the king's death (1346). He then served various members of the French high nobiIity, including John, Duke of Berry, his later years being dedicated to the manuscript compilation of his works. (http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/machaut.html)

Eustache Deschamps

Also called MOREL, on account of his dark complexion; b. at Vertus in Champagne between 1338 and 1340; d. about 1410. After having finished his classical studies at the episcopal school of Reims, under the poet Guillaume de Marchault, who was a canon of Reims, he studied law at the University of Orléans. He then travelled for some time as the king's messenger in various parts of Europe, in Syria, Palestine, and Egypt; in the last country, it is said, he was made a slave. On his return to France he was appointed gentleman-usher by Charles V, and was confirmed in his position by Charles VI, whom he accompanied in that capacity on various campaigns in Flanders.

His numerous poems, ballads, rondels, lays, and virelays are full of valuable information concerning the political and moral history of his time. He was an honest, religious man, and although a courtier was also a moralist who did not hesitate to condemn the injustice and wrongs that he had seen and experienced. His style is somewhat heavy, but it is vigourous and not lacking in grace. (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04748a.htm)

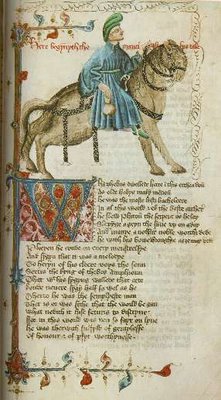

Jean Froissart

French historian and poet, b. at Valenciennes, about 1337, d. at Chimay early in the fifteenth century. The exact dates of his birth and death are unknown, as well as the family from which he sprang. In 1361, after receiving ecclesiastical tonsure, he went to England to present to Queen Philippa of Hainault an account in verse of the battle of Poitiers. This marked the beginning of the wandering life which led him through the whole of Europe and made him the guest of the chief personages of the end of the fourteenth century. His sojourn in England lasted till 1367.

Froissart composed many poems of love and adventure, such as "l'Epinette Amoureuse", in which he relates the story of his own life, and "Méliador", a poem in imitation of the Round Table cycle, etc. His chief work is the "Chroniques de France, d'Angleterre, d'Ecosse, de Bretagne, de Gascogne, de Flandre et lieux circonvoisins", an account of European wars from 1328 till 1400. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06308b.htm

In Chapter Nine, Richard West recounts the story of the the infamous Visconti brothers, rulers of Milan and Pavia, known for their excessive greed and cruelty in fourteenth century Italy. These "Vipers of Milan" represent some of the best examples of historical European decadence, and promulgated a forty-day torture of suspected enemies upon their rule called a Quarentino, using all of the implements familiar to inquisitors, including racks, wheels, strappados, flayings, and other various barbarities. Bernabo is said to have roasted alive four nuns and a monk out of hatred for the Pope. Many historians suspect that Chaucer was in attendance at the marriage of Bernabo's daughter by Regina, Violante Visconti, who married Lionel, Duke of Clarence, a son of King Edward III of England. West makes great fuss over the menu of the wedding feast, describing it as an incongrous mess of ill-paired meats, "crabs with suckling pig, hare with pike, whole calf with trout, capon with carp..." and covered over with a gold leaf gilding mixed with eggs, saffron, and flour.

Clarence died soon after (Perhaps due to the wedding feast meats?). But it turned out to be Chaucer's next job to deliver greetings in the arrangements of another betrothal courtesy of Bernabo Visconti, as everyone sought to try again obviously to renew the English and Italian alliance with another wedding seal, this time Bernabo would marry another daughter, Caternia, to Richard of Bordeaux, son of the Black Prince. West seems to dither over Chaucer's involvement in the goings on of the most reknowned European tyrants of the day, but appears to forget the feckless slaughters of thousands of French peasants and noblemen by English mercenaries during The Hundred Years War for the sake of territories and tax benefits.

Tyrannical-type bosses appear never unfamiliar to Chaucer, considering the English battles to hold Gascony, they paid his salary as a civil servant. In such cases, he appears as many artists do, as gold leaf upon feckless brutish, incongrous barbaric European meats. But even the Visconti brothers were known to feather their bloody nests with the likes of Petrarch, though one wonders when the tyrants of European courts had time to enjoy the flitting pleasures of poets, perhaps before or after they were consuming strange pairings of gold gilded meats, or during pauses in the engaging of sexual manias or orgies, as breaks in the torturing murders of suspected enemies, or even codas to the strangling of young male servants. These tyrants were able to fit fellows like Chaucer in with a few rhyming couplets and alexandrines? When? As some sort of poetic coaches or referees then?

Chaucer makes notable reference to the Visconti brothers in his prelude to The Legend of Good Women and refers to Visconti exploits in the Monk's Tale, but according to West, it is in the Clerk's Tale that Chaucer reveals his feeling on the topic of the Visconti, with reference to Griselda of Petrarch's Decameron, Chaucer produces his own Griselda to perhaps teach that women should make their husbands jealous and spend money, which is described as tongue in cheek. Some women might not require such encouragement. The Clerk's Tale is also represented as a variant of Cinderella, and that in issues of marriage, love and compatability were often not important where the choices of brides for a royal Prince were concerned. West describes Chaucer's Clerk's Tale as a, "homily on patience and obedience".

But in reality it may have just been a double entendre of simple proportions. Borrowing the characters of Petrarch, a pet of the Visconti, an obvious allusion there. Further, concerning the son of the Black Prince, Chaucer's Prince is being goaded into marrying by his subjects. However British subjects of note were peers and knights expecting bridal benefits to include further pillage and rape in France. The wrong bride often meant chump change and thus potentially usurpation. Their expectation that he should marry a high-born woman is finally met, but secretly the Prince has selected a poor country girl. Perhaps this is a symbolic representation of Visconti dishonour, or perceived wealth, or perceived value of the alliance to the aims of conquest in France. But when the public are fooled by his deception, the Prince then punishes Griselda by removing her children to be raised in Bologna. Obviously another Italian connection there. Then the Prince exchanges Griselda for a younger wife, supposedly due to public opinion, but again tricks her as the new wife is actually Griselda's daughter.

It would be interesting to know more about the actual marriage between the Black Prince's son and Caternia, and the finances of the Visconti Brothers. Perhaps Chaucer had secret party to their books, and perhaps they had little to offer the English than spare daughters.

No comments:

Post a Comment