Non-Relative Exemplificationary Evidences of Cultural Descriptiveness (Review Part Six) The Silent Language (Edward T. Hall) 1959

Non-Relative Exemplificationary Evidences of Cultural Descriptiveness (Review Part Six) The Silent Language (Edward T. Hall) 1959My first admission regarding such a monstrous title for this little article is based on my passing usury of amazon reviews to gauge roughly whether or not I should proceed and purchase my next title, long or short. However I reviewed what those readers had to say about this book probably about a year ago or so and I was slightly unimpressed. Too many of those reviews appear tossed off without much in the way of qualifying depth of analysis. So "Joe Blow" says this one is good, that one dry, this cracker is stale, etc. What exactly does "Joe" or "Joanna Blow" actually know? I got in a lot of trouble about a year ago for telling the friend of a friend, "Look, I am not going to let some chick tell me that I do not know what I am talking about." Which to me means that opinions, personal ones, they may be useful in talking about personal preferences, fashion tastes and so on, but not about complex values orientations, or more specifically, the methods by which cultural values systems are effectively hijacked by corporate growth globally and dynamically. I humbly realize chicks are not always ready for such perspectives. Not without further qualification.

It seems often the reviews one finds on book-sellers sites are notably brief and usually hastily assembled pronouncements upon diverse topics. Sound familiar? In particular, one reviewer was quick to dismiss Hall's theories as a bit dated based on examples he used to describe early attempts at describing patterns differences among Japanese businessmen assembling in The USA at the turn of the century. Hall had referred to antiquated status setting among American men for example and the sharing of cigars in particular and so on to determine patterns of informal or hierarchical cultural standards setting. Some readers fairly dismiss relevancy based on such a shallow reading or interpretation of the arguments Hall has put forth in this text. Ditto for anything longer than a page in TV Guide these days?

OK, sure there are few cigar chomping businessmen out there today among the herd-like sterility espoused in the standardized modern Starbucks Coffee Houses mentality-set and their blanketing of all healthy values with their own specialized, self-satisfying, deluded, marketing terms such as "well-being", "dolphin-friendly", or the most erronously famous, "Not tested on animals." Ask the WTO about the fishermen who swear they saw no dolphins when they canned that tuna. However, the

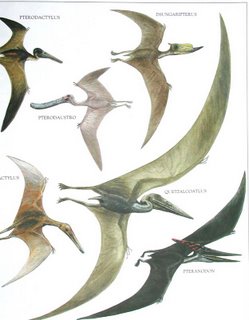

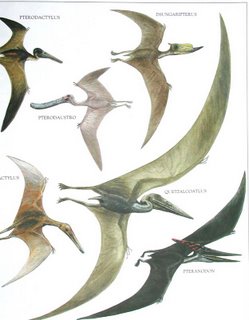

paleontologist does not begin to critically dismiss whole portions of the fossil record out of, for example, status quo "Beetle-Bop Man On the Street" claims that a

pterodactyl's wings are too wide to have been useful for early reptilian flight. Few critically claim that systems such as MS Dos have no use to the current generation of systems which collect and arrange themselves as a house of cards upon its basic, pondering, slow and susceptible to crashing nature. Complicated concepts just get more dissing.

So too, one should not disregard the early, perhaps rudimentary systems of analysis of cultural comparitives which helped spawn this mangy and great global macro-economic corporate universe called modern international business today. Without those cigar chompers and analysts, and methodological analysis of such things, many creature comforts, perhaps primarily those due to perceptual inabilities (stubborn unwillingness) to formulate logic-based individual research or "bony flight" in the areas of cultural comparatives among the strictly New York Times Crossword completers, many things like WWW would probably not exist as we take it for granted daily. Let some stoning begin? Not exactly. Let that opinionated chick know it takes more than an opinion to assemble and profit from cultural comparatives. Let that chick spend years of her life rolling over research stones to see what wiggles and squeaks down there under her toes and seemingly beyond her past or current frames of experience to at times take my roving word for it.

Learning is more often about being wrong than right and in my case chicks do not like being referred to in the third person. Nor do they like being called chicks anymore I guess. Ask me if that is not equally true for teaching. It is the perpetual log in one's own eye which each should be reaching for fundamentally to grasp new, challenging, or unfamiliar topics or how to disseminate them. Fop Siderius, my neighbourhood school bus driver from decades past was a considered motivator one summer who teaches me still. Dreading every day of jazz band music practice due to difficult new notes and rifts, I admitted to him alone that I just wanted to quit and never go back. He kind of scrunched his eyebrows together and said, "Danny if everything was easy would you want to do it? Then you would be bored." So above everything else at this time I remember that in reference to attempts at simplifying in my own mind what already appears fairly simply written by Edward T. Hall in "The Silent Language."

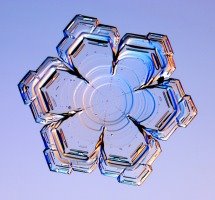

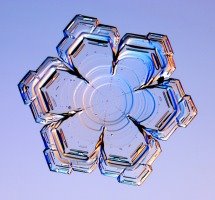

Namely where are the patterns of culture within which one resides and with which one may compare, specifically if the samples up for comparison are determined historically at different rates of relative values, on scales of variation within which in themselves changes in relevancy are in complete dependance upon current filtered concepts of what constitutes cultural relatedness on a historically perceived scale of development in terms of patterns? I think such examples as the dated cigar chompers fairly prove the point that cultural patterns really are out there in such layered conceptions, too quickly dismissed as irrelevant to the present reader perhaps on a smoothly cracked, surface type analysis. Am I taking the snowflake symbolism a little too far here? Stubbornly I think not. Plus they are fairly beautiful to analyze and even just appreciate as themselves. They hover for a moment and then are gone. Cultures are composites of such individual perceptions.

Similarly I believe humans easily assemble patterns of cultural values through environmental influences which are continuously recompared to status quo norms, contexts and events, which are then reaffirmed or discarded, among many, through the general prospects of peer pressure influences or concensus-building efforts which implicate the old debate on the actual terms of insanity or sanity at conscious and unconscious levels. Particularly how much of conscious self is actually a filtered cultural precept? Communal values allow a certain flexibility in the determination of same or different. Though the individual may waver along a context of the formally familiar, points and borders of acceptable formality and samenesses or differences exist. So Hall discusses three sets of organizing patterns in culture.

Namely, patterns are highlighted within characters like the tired cigar-chompers as exemplifiers of status and a facet of a first formal and hierarchical organizing precept. It exists among individuals as amorphous thematics and provocation of conflicts among some, defined by evolving rates of competitiveness over time, particularly the corporate kind which increasingly appears only to value status defined by increasing focus on outstanding displays of increased sales rates, growth rates, or productivity rates. To the extent that the standards of acceptable variation, among human individuals in a working environment, are increasingly applied and pressured to meet lean-time or JIT concepts of zero defects possible only among computers or super-workers, an impossible outcome on general human terms of falliability. Structurally formal patterns only reveal themselves when an individual is perceived to have broken any of them. So corporate cultural precepts of status, as their bloated heads reveal, have taken on a whole new method of driving cultural perspectives on success which would make Fredrick Taylor envious.

Hall then goes on to illustrate the formality of cultural patterns with an example concerning Middle Eastern bargaining patterns. Often this example feels familiar to me due to my work experience in the Middle East and the context Hall portrays makes me suspect that he was mostly hanging around busy tourist markets scribbling on a postcard where his model would be obviously relevant. My own experience of local markets leads me to generally apply market principles which he has possibly not noted.

Firstly, any bargainer who does not know the market price for a product especially in the Middle East is obviously going to get scalped. The only way to really buy in the Middle East, in my humble opinion, is to window shop profusely. Very carefully observing the way by which a salesman accepts your bargaining behaviour or comparison shopping, the more quickly one may determine the bargaining process through which Hall exemplifies cross-cultural concessionary and negotiating conduct. Then, in my experience I have evolved repeat business to the same seller over a period of years to maximize the trade relationship which is determined by a personal commitment to repeat business in many developing nations and minimize future prices. A first price is often not a determinant of value, as well, a first purchase is almost never a determinant of future prospective best prices. One must often simply choose carefully the seller worth repeat business to maximize value.

Hall examines the canard of the Aswan Dam bargaining process by which an originally American-backed project was gunneled out for Russian backing instead. The second aspect of hierarchical patterns, those considered informal are even harder to imagine than the formal ones, similar to the impact of coming up upon a vast lake in the middle of an even vaster desert, as on a direct flight down The Nile to Abu Simbel where Lake Nasser persistently shimmers and evaporates. He posits that rules for grammar, for example the can-may distinction can be traced to cultural values once applied to the polite speech apportioned to men or women in western societies, which remain informally fairly distinctive, but through which formal constructions of cultural grammar determinations have been based. Thrown or rolled out upon and interwoven (or under) the worked patterns akin to hundreds of stitches per square inch that one may carefully discern in a qoom carpet reflect gathered, silken ties of technical cultural underpinnings discernable (?) in patterns.

Ordering Patterns

Then Hall determines that laws of order exist which define culture similarly to meanings such as: "The cat caught the mouse." Word formation and sentence formation exemplify cultural orders such as those of birth, lining up for tickets, dinner courses, etc. He tips lightly upon the cross-cultural challenges in terms of order-taking for westerners in foreign countries, order according to status often not in a first-come first-served basis. He notes Pueblo societies often order according to people, situations, or status but rarely simultaneously. These would illustrate diversity of order normatives.

Selection Patterns

Combinations of sets are determined in selection determinants such as which side of the road cars drive upon, which may change over time and implicate patterns with knots and frays where selection most applies. Describing buffet breakfast options and the variations available on a regional basis exemplifies that people may all eat breakfast as a repetitive pattern but not always the same components of foods, so too in cultural selection patterns. This implicates global patterns of primary message systems according to Hall where custom versus logic may most dictate a particular pattern. It demonstrates arbitrary binding to a culture with little room for variation.

Congruence

The most difficult to perceive according to Hall is the congruence patterning of culture or the patterning of patterns. He claims it is exactly what writers seek in the expression of voice, and implies human reactions similar to awe or ecstasy, which explains my fondness for simplification of these terms and ideas with patterns type images, large chunk-like reference points for the human mind to perhaps elementally grasp Hall-ist patterns descriptions which might otherwise feel or seem quite pedantic.

A devoidness of congruence would appear fairly unworldly to any member of a culture. Hall expresses congruence in terms of dress and clothing standards, for example an Inuit would not show up at the blow hole with a loin cloth. He also posits that incongruity is often the basis of many jokes which require native proficiency in a language to find the humour in them (particularly if the joke is actually funny as often they rarely are anyway).

Hall makes one of his funniest comments regarding congruity in terms of mediums of literature and context. For example the styles of expression in writing is often determined by the discipline, be it newspaper or journalistic writing versus scientific writing or typical froth-blog platitudes type fluff, diary topics, or the most boring of types, the exploratory or expositional review-type blog. He quotes Harry Stack Sullivan, a once prominent psychiatrist as describing his own attempts in writing as imagining that his sentences appraiser was a cross between, "an imbecile and a bitterly paranoid critic. " Coincidentally, does that describe you? Or me?

Hall then goes on to explain extreme congruity is rarely achieved on a cultural level, where everything fits between communicator and intended audience (note critics and imbeciles). Thus he considers that when it does come about it is the result of true artistry, exhibited in cultural intangibles, masterpieces in art, literature or sculpture which touch heavily upon some congruence, perhaps the inhabited silences of immortality which artists tend to occupy. I would dare to say our corporate global entities are squeezing much out of the mantra, "I'm not like everybody else" a little too heavily for it actually to be completely true these days. How many living artists or individuals have a right to justly unproven (by centuries of cultural weathering) congruent eloquence? To believe I understand it proves little of congruent value and much of corporate insistence that I indeed be exactly like everyone else. Realizing this who thus accrues profits?

Getting Closer to The Point: Hall On Time and Proxemics (Review Part Nine)

Getting Closer to The Point: Hall On Time and Proxemics (Review Part Nine)

Variety

Variety Hall posits that with variety time passes more quickly and conversely that it passes more slowly with sameness. He makes the statement that imprisonment in a place devoid of light without a sense of the passage of time, or the distinctions between night and day will provoke disorientation and the "loss of one's mind". Hall also observes aging as a process of variety often only observed in the context of the observing of the aging of others rather than self. As for Hall's discussions on time, they age well, such distinctions retain relevancy on an anecdotal basis a mere forty-seven years after they were first penned.

Hall posits that with variety time passes more quickly and conversely that it passes more slowly with sameness. He makes the statement that imprisonment in a place devoid of light without a sense of the passage of time, or the distinctions between night and day will provoke disorientation and the "loss of one's mind". Hall also observes aging as a process of variety often only observed in the context of the observing of the aging of others rather than self. As for Hall's discussions on time, they age well, such distinctions retain relevancy on an anecdotal basis a mere forty-seven years after they were first penned.