Chaucer correctly, and firstly, likened his English language to the miracle weapon of the day, the longbowman, able to propel darts and arrows of greater strength further and faster, mostly into ranks of French knights and their mercenary allies, the Venetians, as evidenced by the skirmishes and semi-victories of The Hundred Years Wars on the continental kingdoms of a France not yet resolved as a nation. It is a paradox that he proceeded to steal their cultural themes, as his compatriots raided their lockboxes and material possessions.

But prior to this time, the French language was also the language of Britain. A good accounting is found in, "A History Of The English Language" (Baugh and Cable: 2002), an extremely important little book which by some accident, the wise bookseller in the depths of 'Han Byul Kwan' had seen to stock his shelves with after my earliest visits to his English section back in the late 1990s. These were the days before internet. Chaucer's evidences for striking back at French literature are found from his participation in battle in 1359 at Reims, the results of which influenced other poets to record the trials of never-ending border battles, such as Eustache Deschamps, who wrote this Ballade always from the opposing view:

In Antwerp, Bruges, Ostend and Ghent

I used to order food with flair,

But in every inn to which I went

They always brought me, with my fare,

With every roast and mutton dish,

With boar, with rabbit, pigeon, bustard,

With fresh and with salt-water fish,

Always, never asking, mustard.

I ordered herring, said I'd like

Carp for supper at the bar,

And called for simple boiled pike,

And two large sole, when I ate at Spa.

I ordered green sauce when in Brussels;

The waiter stared and looked disgusted;

The bus boy brought in with my mussels

As always, never asking, mustard.

I couldn't eat or drink without it.

They add it to the water they

Boil the fish in and-don't doubt it-

The drippings from the roast each day

Are tossed into a mustard vat

In which they're mixed, and then entrusted

To those who bring-they're trained at that-

Always, never asking, mustard.

Prince, it's clear a spice like clove

can drop its guard. It won't be busted.

There's just one thing these people serve:

Always, never asking, mustard.

Now Koreans might know what kimchi at every meal might feel like to foreigners? As West recounts in an excerpt from 'Ballade of the Domain of Eustache', 'brule par les Anglais', the French were embattled into becoming a nation by the English:

Outside Vertus stands a gracious house

Where I have lived a long time

And where many others led happy lives

House-of-the-fields it was often called

But full of corn, thanks be to God.

Now the English have put it to the torch

Two thousand francs their war has cost me.

From now on I'm known as Burnt-out of the Fields.

Chaucer carried these battles to the language in words, and fortified English written text as a medium through which the English themselves could bind the times to the words which were written for and about it and them. For the first time. But as the 'bastarde' language that it is, Chaucer reaped from the writings of foreigners as the language itself continues to do, and made great gains by adapting the themes of the 'Roman de la Rose', written by two French authors in the 13th century. A website which briefly explains its significance to European cultural history can be found at The University of Glasgow Library.

http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/month/feb2000.html

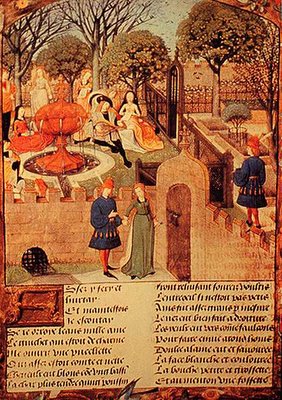

This Roman was France's first reknowned pictorial dirty book. It was considered by critics as base, sordid, and as such, took on a titalating quality among the English, telling a tale of graphic seduction, even feminists of the time (yes, proof they are not a new entrant to the world of literary and cultural critics) among them, Christine de Pisan considered the Roman to be, "a handbook for lechers...a cunning trap to deceive a foolish demoiselle". It helps explain why French are considered experts on love-making, but at the same time suggests that they were merely the first in Europe to widely write and read about it.

But here again, literature depicts its themes by prickly methods, in the 'Roman de la Rose' there is much strolling and lollying about and plucking of garden rosebuds and preening of symbolic healthy young rosebushes, all of this was construed with greater intention than horticultural interests or green thumbs would admit. What was being said was quite nakedly being read. In English. For the first time. In some ways, it depicts the several double-standard types of interests illicit lovers are requested to employ, but at the same time requesting obeyance to the admonishing requirements of chivalry and odes to good conduct, as related in the Kama Sutra. But these were the same ruddy, base, but satisfying themes which Chaucer employed in The Canterbury Tales for the general English, lecherous thus, reading public to ogle.

It is The Wife of Bath who arrests so many readers, writers, and critics, in so many apoplexies, but Chaucer borrowed much of the content of his characters' texts and glosses to such an extent that to which he gained the interests of such diverse qualities of symbolic intent in itself should be credited to his travels, and knowledge of the readings and writers available to him. As a disciple of the classics, especially noted by West, in his understanding of Virgil, Ovid, and Boethius, through such insights were the renaissant, flowering visions of the newly Christian European world borne in, naturally having been built upon pagan and classical underpinnings which had tailored before it.

The over-arching accomplishments of Roman Civilisation had been maintained in its legal systems at the city state levels initially since the demise of The Roman Empire. Hence Chaucer employed the characters and themes of Dante's "Inferno" in his own "House of Fame" and "The Legend of Good Women" to some comic effects, such as eagles complaining about the weight of souls. This would lead the reader to wonder to what end Chaucer sought to define the arrival of English Literature. His efforts delivered laughter to his readers and to their language its wholely researched first farces, and tragic-comedies. As such he stands as the first Italianate Englishman.

No comments:

Post a Comment